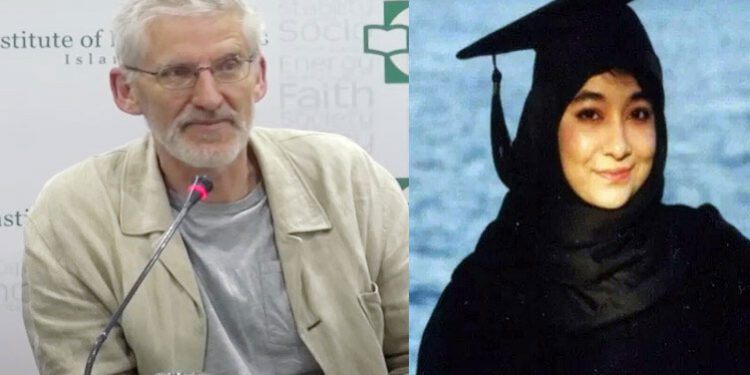

After more than two decades of silence, courtrooms, and controversy, the case of Dr. Aafia Siddiqui is once again making headlines. Her American attorney, Clive Stafford Smith, is scheduled to arrive in Pakistan on May 4 to participate in legal proceedings regarding her repatriation—a move that could reignite one of the most polarizing and emotionally charged legal sagas in U.S.-Pakistan relations.

For years, Dr. Siddiqui’s name has symbolized injustice, mystery, and failed diplomacy, depending on who you ask. But as international interest resurfaces and legal momentum builds in Pakistan, this moment demands a sober, fact-based reassessment of what this case represents—and what is at stake going forward.

A Case Mired in Contradictions

Born in Karachi in 1972, Aafia Siddiqui was once seen as a symbol of academic excellence. She earned a PhD in neuroscience from Brandeis University in 2001 and was living in the United States until the early 2000s. In 2003, shortly after the arrest of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM)—the mastermind of 9/11—Dr. Siddiqui disappeared in Karachi along with her three children. At the time, she was reportedly married to KSM’s nephew, fueling speculation of her association with al-Qaeda.

Five years later, in 2008, she resurfaced in Afghanistan under highly contested circumstances. U.S. officials claimed she was detained in Ghazni, allegedly in possession of documents describing attacks on U.S. targets and dangerous chemicals. During her interrogation, she was accused of grabbing an American soldier’s rifle and opening fire—a claim that became the basis of her 2010 conviction in a New York court for attempted murder and assault.

Notably, Dr. Siddiqui was never charged with terrorism, a detail often overshadowed by the media branding of her as “Lady Al-Qaeda.” The case rested on an alleged moment of violence, not on evidence of her involvement in any actual terrorist plot.

She was sentenced to 86 years in a U.S. federal prison, a penalty that drew widespread criticism from human rights advocates, legal experts, and many in Pakistan. Concerns were raised about the lack of forensic evidence, inconsistencies in testimonies, and most of all, the legal conditions under which she was held and tried.

A Diplomatic Deadlock

Over the years, Pakistan’s efforts to secure her release have been inconsistent and largely symbolic. Successive Pakistani governments have cited her case to appease public sentiment but have failed to offer sustained diplomatic pressure or leverage international legal channels effectively.

A recent proposal to exchange Dr. Siddiqui for Dr. Shakil Afridi—a Pakistani doctor imprisoned for assisting the CIA in locating Osama bin Laden—was rejected by Pakistan’s federal government. While the U.S. has shown no interest in negotiation, Pakistan too has lacked a cohesive legal and diplomatic strategy.

Now, Clive Stafford Smith’s arrival in Islamabad signals a potentially serious shift in how the case is approached. Smith, known for his human rights advocacy and work with Guantanamo detainees, is expected to work closely with Dr. Siddiqui’s local counsel Imran Shafique. Their aim is to build a stronger case for her repatriation under international legal norms or bilateral arrangements.

The Islamabad High Court, during a recent hearing, postponed proceedings until May 6 to allow for consultations with Smith. Whether this move marks a serious legal opportunity or yet another procedural delay remains to be seen.

Public Sentiment and the Human Rights Angle

In Pakistan, Aafia Siddiqui remains a deeply symbolic figure. For many, she is a national daughter wrongfully imprisoned, a victim of the post-9/11 dragnet, and a casualty of American overreach. Others view the case with more caution, noting the complex allegations and opaque history that continue to surround her disappearance and reemergence.

Still, there is no denying the severe human rights concerns raised over the years—both regarding her disappearance between 2003 and 2008, and her treatment in U.S. custody. Reports of solitary confinement, limited access to legal counsel, and deteriorating mental health have only intensified calls for her return.

International human rights organizations have long argued that her trial did not meet fair standards of justice. Questions remain unanswered: What happened during the five years she was missing? Where were her children? Why was she charged only with attempted murder but not terrorism, despite years of public speculation? These gaps in accountability continue to fuel distrust in the process that led to her incarceration.

What Comes Next?

The May 6 hearing may offer the Pakistani government a renewed opportunity to take a clear position on the case—one that aligns with its legal obligations and the demands of justice, rather than mere political expediency. For the United States, the case remains an example of a broader post-9/11 legal framework that prioritized counterterrorism over due process.

If repatriation is even possible, it will require far more than a courtroom appearance. It will demand diplomatic resolve, legal clarity, and above all, a willingness to revisit a case that many would rather forget.

But forgetfulness is not justice.

Conclusion: A Mirror to the System

The case of Aafia Siddiqui is not just about one woman—it is about how justice is negotiated between nations, how political expediency often trumps legal ethics, and how silence can be a tool of oppression. As Clive Stafford Smith steps into Pakistan next month, the world should pay close attention—not for spectacle, but for the principle.

Because in the end, how we treat cases like Aafia Siddiqui’s says more about us than it does about her.