Over the past few decades, workplace safety has dramatically improved in many parts of the world, ensuring healthy working conditions for many individuals.

There is still much need for improvement, as seen by the collapse of Rana Plaza, a nine-story building in Bangladesh that housed many garment workshops that were largely tied to the fast fashion sector, ten years ago.

According to research cited by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2.8 million individuals lost their lives on the job in 2017 alone, and an additional 374 million people experienced non-fatal injuries.

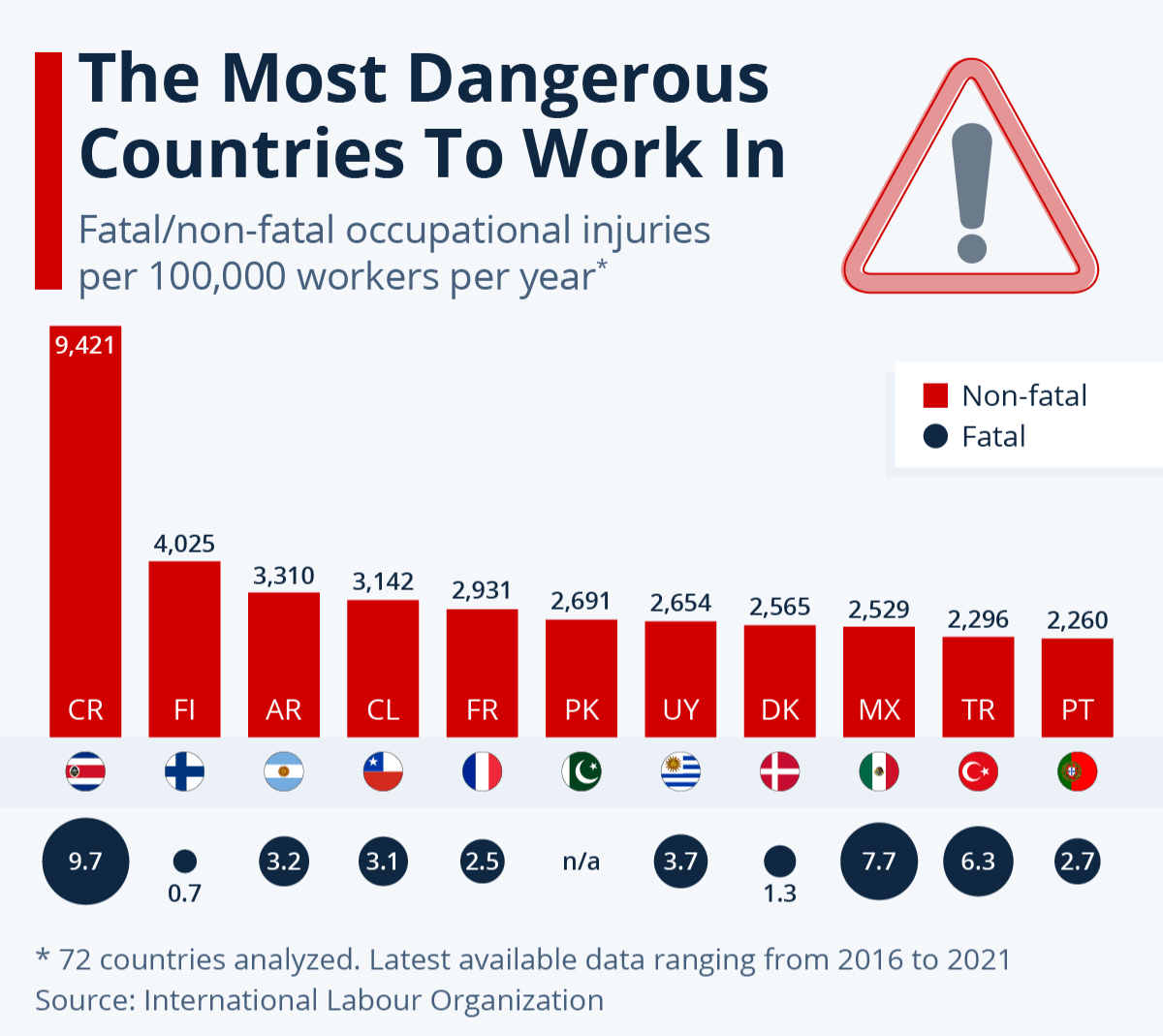

With 9,421 non-fatal and 9.7 fatal occupational injuries per 100,000 workers in 2016, Costa Rica now has the highest rate of work-related injuries, according to ILO data.

The economy of the country has been mainly reliant on agricultural and tourism for many years. With significant investments made in the nation by businesses like Intel and Procter & Gamble, manufacturing and industry have eclipsed the agricultural sector since the turn of the millennium.

In 2006, twenty percent of all exports from Costa Rica and five percent of the nation’s GDP were attributed to Intel’s microprocessor plant, according to news reports.

The aforementioned emphasis on industry and manufacturing may also be to blame for the high rate of fatal occupational injuries, according to anecdotal data from other nations.

Mexico and Turkey, who are ranked ninth and tenth in terms of non-fatal injuries as well as second and third in terms of fatal occupational injuries, provide separated statistics on fatal injuries by economic activity, but Costa Rica does not.

For instance, 118 persons died in the manufacturing sector in Mexico out of 806 work-related deaths, 76 in the construction industry, and 86 in the transportation and storage industry. Out of a total of 1,394, Turkey recorded 386 deaths in building, 297 deaths in manufacturing, and 258 deaths in transportation and storage.

Pakistan and Portugal, two countries known for their textile industries, are among the top 10 nations for occupational injuries per 100,000 workers.

Although the labour practises and working conditions in the fashion industries of the aforementioned countries are constantly reviewed and approved by outside auditors, the reality is frequently much worse than official assessments show.

For instance, a 2019 study by the NGO Human Rights Watch on Pakistan’s garment workers highlights employers’ failure to pay workers the minimum wage, the absence of written contracts, the dismissal of pregnant workers, and pay deductions for sick days.