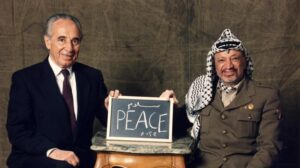

On a sunny day in Washington, D.C., on September 13, 1993, the world witnessed an unprecedented moment that promised to reshape one of the most intractable conflicts in modern history. Under the eyes of U.S President Bill Clinton, two lifelong adversaries—Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat—shook hands in a historic moment that seemed to encapsulate the spirit of hope and reconciliation. This handshake was the symbolic climax of the Oslo Accords, a framework painstakingly negotiated in secret in Norway and hailed as a breakthrough in the path to peace between Israel and the Palestinian people.

Yet, despite the fanfare and high hopes, the Oslo Accords were far from a comprehensive peace agreement. Instead, they were an attempt to manage a complex conflict that had persisted for nearly a century, marked by territorial disputes, ideological differences, and bloodshed. Oslo was, in essence, a diplomatic experiment—a framework meant to incrementally lead to the resolution of some of the thorniest issues in the conflict. But as the dust settled and the ink dried on the documents, the real struggle was just beginning.

Nearly three decades later, the Oslo Accords are viewed by many as a failed experiment—a lofty diplomatic endeavor that was ultimately undone by political miscalculations, bad faith negotiations, and deep-rooted mistrust. To others, the Accords still offer a glimmer of hope, a foundational framework that—if revived and reformed—could still serve as a path toward peace. The truth, as with most things in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, lies somewhere in between.

Oslo Accords: The Framework and Key Provisions

The Oslo Accords, officially known as the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, were never intended to be a full peace agreement. Instead, they laid out a series of phased steps aimed at building trust and moving the two sides toward a final resolution. At their core, the Accords aimed to establish a framework for negotiations on the final status of issues such as borders, the future of Jerusalem, the fate of Palestinian refugees, and the status of Israeli settlements.

The Accords in Brief:

- Mutual Recognition: For the first time in the history of the conflict, the PLO recognized Israel’s right to exist in peace, and in return, Israel acknowledged the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. This mutual recognition was groundbreaking, signaling the first formal acknowledgment of the other’s legitimacy and a willingness to engage in direct dialogue.

- Creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA): The Accords called for the establishment of an interim self-governing body for Palestinians in parts of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This body, the Palestinian Authority (PA), would be responsible for administering Palestinian cities and towns and managing daily affairs such as education, health, policing, and local governance. Over time, the PA would assume greater responsibility, paving the way for eventual Palestinian sovereignty.

- Phased Israeli Withdrawal: Under the terms of the Accords, Israel agreed to gradually withdraw its military forces from areas of the West Bank and Gaza that were heavily populated by Palestinians. In exchange, the PA would take over security responsibilities in these areas. Key cities such as Ramallah, Hebron, Nablus, and Bethlehem were included in the areas to be transferred to Palestinian control.

- Negotiation of Final Status Issues: Perhaps the most significant, and most problematic, aspect of the Accords was the agreement to postpone discussion of the most contentious issues—Jerusalem, the right of return for refugees, Israeli settlements, and permanent borders—until later negotiations. These were labeled as “final status” issues, to be addressed after confidence-building measures were implemented.

The Oslo Accords, in essence, represented a process, not an endpoint. They were meant to create momentum toward peace, with the understanding that the final destination—an independent Palestinian state and the resolution of key disputes—would be determined through further talks.

Context of the Oslo Accords: Why 1993 Was a Moment of Opportunity

To understand why the Oslo Accords happened when they did, it is essential to look at the geopolitical landscape of the early 1990s. The Cold War had just ended, reshaping global power dynamics and creating new opportunities for diplomacy. The Soviet Union, long a backer of Arab states in the conflict, had collapsed, reducing the pressure on Israel from that quarter. Moreover, the First Gulf War in 1991 had highlighted the strategic importance of U.S.-Israel relations, while also demonstrating the limitations of the PLO’s influence after Arafat had aligned with Saddam Hussein—a move that cost him crucial support from the Gulf states.

At the same time, on the ground, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had reached a point of exhaustion. The First Intifada—an uprising of Palestinians against Israeli military rule that began in 1987—had inflicted heavy casualties on both sides, and the violence showed no signs of abating. Israeli policymakers, faced with the growing international condemnation of their handling of the Intifada, and the high cost of maintaining the occupation, began to reconsider their approach.

For the Palestinians, the PLO was facing increasing pressure from the newly formed Hamas, which was growing in influence in the Gaza Strip. Arafat needed a way to reassert the PLO’s leadership of the Palestinian cause and demonstrate to his people that he could deliver tangible gains. The Oslo negotiations, therefore, represented a convergence of necessity and opportunity for both sides.

The Oslo Accords: Historical Context and Preceding Attempts

The Oslo Accords were not the first diplomatic effort to bring peace between Israel and the Palestinians, but they represented the most significant breakthrough up to that point. Prior to Oslo, the Camp David Accords of 1978, mediated by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, had successfully brokered peace between Israel and Egypt, but did little to address Palestinian aspirations for statehood.

The Madrid Conference of 1991, convened by the United States and the Soviet Union, brought together Israel, the Palestinians, and neighboring Arab countries in a multi-lateral setting. Though the Madrid talks failed to produce a peace agreement, they laid the groundwork for future negotiations by establishing direct dialogue between the Israelis and the PLO.

Secret Diplomacy in Norway: How Oslo Came to Be

While the official, U.S.-backed peace talks in Washington faltered, a secret backchannel negotiation emerged in Norway. Norwegian diplomats, including Terje Rød-Larsen and Mona Juul, played a key role in facilitating clandestine meetings between Israeli and Palestinian representatives beginning in early 1993.

The talks were originally intended to address practical matters of coexistence, but they quickly evolved into a broader negotiation about the future of the Israeli-Palestinian relationship. The participants—on the Palestinian side, led by Ahmed Qurei (also known as Abu Ala), and on the Israeli side, by Yossi Beilin and Uri Savir—hammered out the framework that would become the Oslo Accords.

Key Players: Rabin, Arafat, and Clinton

The Oslo Accords could not have been achieved without the bold political leadership of key figures. Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s prime minister, took a significant political risk by engaging with the PLO—a group that had long been considered a terrorist organization by many Israelis. Rabin, a decorated military leader, understood the weight of security concerns but recognized the need for a diplomatic resolution to the conflict.

For Yasser Arafat, chairman of the PLO, the Oslo Accords were a lifeline. By the early 1990s, Arafat’s political standing was waning, especially after his controversial support for Saddam Hussein during the First Gulf War. Oslo gave Arafat the opportunity to return to prominence, both domestically and internationally, as the leader who could deliver on the promise of statehood.

U.S. President Bill Clinton played an essential mediating role, hosting the signing ceremony on the White House Lawn and providing crucial political and financial backing to the peace process. Clinton’s involvement added international legitimacy to the negotiations, and he worked tirelessly to keep both sides at the negotiating table in the years following Oslo.

The Oslo II Agreement (1995): A Step Forward or a Stumbling Block?

The Oslo II Agreement, signed in September 1995, was a follow-up to the original accords, further elaborating on the process of transferring authority to the Palestinian Authority (PA). Oslo II divided the West Bank into three distinct zones:

- Area A, under full Palestinian civil and security control;

- Area B, under Palestinian civil control but shared Israeli security responsibility;

- Area C, under full Israeli control, which included Israeli settlements and security zones.

Though Oslo II expanded Palestinian autonomy, it also formalized the division of the West Bank, leaving much of the territory under Israeli control. This bifurcation led many Palestinians to see Oslo II not as a step toward independence but as a form of continued occupation in a new guise.

Settlements and the Erosion of Trust

One of the biggest failures of the Oslo process was its inability to address the issue of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. At the time of the signing of the first Accords, the number of settlers in the West Bank was relatively low, around 110,000. However, instead of freezing settlement construction, the settler population continued to expand under successive Israeli governments.

By 2024, more than 700,000 Israelis lived in settlements across the West Bank and East Jerusalem. To Palestinians, the expansion of these settlements represents a direct violation of the Oslo spirit, eroding trust in the peace process and making the possibility of a contiguous Palestinian state ever more remote.

The Role of Hamas and Extremist Violence

While the Oslo Accords were a political triumph for Yasser Arafat and the PLO, they were deeply unpopular among more radical factions of Palestinian society, particularly the Islamist group Hamas. Founded in 1987 during the First Intifada, Hamas rejected Oslo’s vision of a two-state solution, instead advocating for the complete liberation of all Palestinian territories, including pre-1967 Israel.

Hamas launched a series of suicide bombings and terror attacks targeting Israeli civilians throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, undermining the Oslo process and hardening Israeli public opinion against further concessions. For many Israelis, the rise of Hamas demonstrated that the Palestinians were not unified in their pursuit of peace, casting doubt on the viability of the Palestinian leadership under Arafat.

Yitzhak Rabin’s Assassination: A Tragic Turning Point

The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995, by a right-wing Jewish extremist, Yigal Amir, is often seen as the beginning of the end for the Oslo process. Rabin’s death dealt a severe blow to the peace process, removing its most powerful Israeli advocate.

Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres, tried to continue the Oslo path but lacked Rabin’s security credentials and political capital. When Benjamin Netanyahu, a staunch critic of the Accords, was elected in 1996, he further stalled the peace process, focusing instead on security measures and expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

The Second Intifada: Oslo’s Final Undoing

The outbreak of the Second Intifada in September 2000 marked the violent collapse of the Oslo process. Triggered by Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon’s controversial visit to the Temple Mount (known to Muslims as Haram al-Sharif), the Second Intifada was characterized by widespread violence, including suicide bombings, Israeli military incursions, and mass protests. Over 3,000 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis were killed in the fighting, which lasted until 2005.

The Second Intifada dashed any lingering hopes that the Oslo Accords could deliver peace. By the end of the uprising, both sides had become entrenched in their positions, with Israel constructing the Separation Barrier in the West Bank and Palestinians increasingly turning to Hamas for leadership.

Hope and Optimism: The Early Successes of the Oslo Process

In the immediate aftermath of the signing, the Oslo Accords did produce some notable successes. The Palestinian Authority was established, and Arafat returned to the West Bank and Gaza Strip after decades of exile, greeted as a hero by many Palestinians. Israel withdrew from key Palestinian cities, and in 1994, a follow-up agreement, often referred to as Oslo II, was signed. This extended Palestinian self-rule to other parts of the West Bank, including Hebron, a city with deep religious significance and a volatile mix of Israeli settlers and Palestinian residents.

The atmosphere during these early years of the Oslo process was one of cautious optimism. International donors, including the United States, European Union, and Japan, poured billions of dollars into the fledgling Palestinian Authority, funding infrastructure projects, schools, and governance reforms. The Paris Protocol—an economic agreement attached to the Oslo framework—was designed to boost the Palestinian economy, linking it to the Israeli economy in mutually beneficial ways.

Meanwhile, regional diplomacy flourished. The 1994 Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty—a direct outgrowth of the momentum created by Oslo—cemented Israel’s relations with another of its Arab neighbors. The possibility of a new Middle East, one where Israel could coexist peacefully with its neighbors, seemed more tangible than ever.

A Slow Unraveling: Assassination, Violence, and Political Intransigence

Yet, beneath the surface, cracks were already beginning to show. Oslo’s phased approach, which delayed the discussion of final status issues, meant that many of the core grievances on both sides festered rather than being addressed. For Palestinians, the ongoing expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank was particularly galling. The number of settlers in the West Bank continued to grow, despite Israeli promises to freeze settlement activity, creating what Palestinians saw as a de facto annexation of their land.

Meanwhile, in Israel, opposition to the Oslo process was growing, particularly from right-wing and religious sectors. Many Israelis viewed the Accords as a dangerous gamble that put the country’s security at risk. Tensions boiled over on November 4, 1995, when Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister and architect of the peace process, was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a Jewish extremist opposed to territorial compromise. Rabin’s death dealt a crippling blow to the peace process, shaking Israeli society to its core and elevating voices that opposed Oslo.

In the Palestinian territories, the peace process faced its own obstacles. While the Palestinian Authority was taking control of cities and towns, the rise of Hamas, a militant Islamist group that rejected the Oslo process, threatened to derail the diplomatic efforts. Hamas launched a series of suicide bombings and attacks against Israeli civilians, sowing terror and reinforcing the narrative among Israelis that the Palestinians were not sincere partners for peace.

The election of Benjamin Netanyahu as Israeli prime minister in 1996 marked a further shift away from the Oslo framework. A critic of the Accords, Netanyahu adopted a more confrontational stance toward the Palestinians, expanding settlements and placing new security measures on the movement of people and goods in the West Bank.

Legacy of Oslo: A Peace Process in Limbo

The legacy of the Oslo Accords is deeply contested. To some, they represent a failed peace process that was doomed from the start, given the deep-rooted grievances on both sides and the unwillingness of either party to compromise on final status issues. To others, Oslo remains the only viable framework for peace, one that could be revived if the political will were found.

The Palestinian Authority still exists, but its authority has been severely diminished, particularly since Hamas took control of Gaza in 2007. Israeli-Palestinian negotiations have stalled for years, and the expansion of settlements has made a two-state solution increasingly difficult to envision.

30 Years On, What Remains?

Today, Palestinians look back on the Oslo Accords with a mixture of nostalgia and frustration. What was once seen as the pathway to independence has instead become a symbol of lost opportunity. Thirty years later, Palestinians are still stateless, trapped in a cycle of occupation, conflict, and division.

The dream of statehood may not be entirely dead, but it has certainly been deferred. For the millions of Palestinians who live under occupation, the question remains: how much longer must they wait for the promises of Oslo to be fulfilled?

Related stories:

UN Expert Warns Israel on Track to Exterminate Gaza Population

Countries imposing ban or restrictions on arms sales to Israel

Countries Supplying Fuel to Israel for Palestinian Bombardment

EU foreign policy chief tables sanctions on hardline Israeli ministers for hate crimes

Israeli military says it killed local Hamas commander in West Bank

US Official for Israel-Palestine Affairs Resigns Amid Gaza Conflict

For more details about the history: