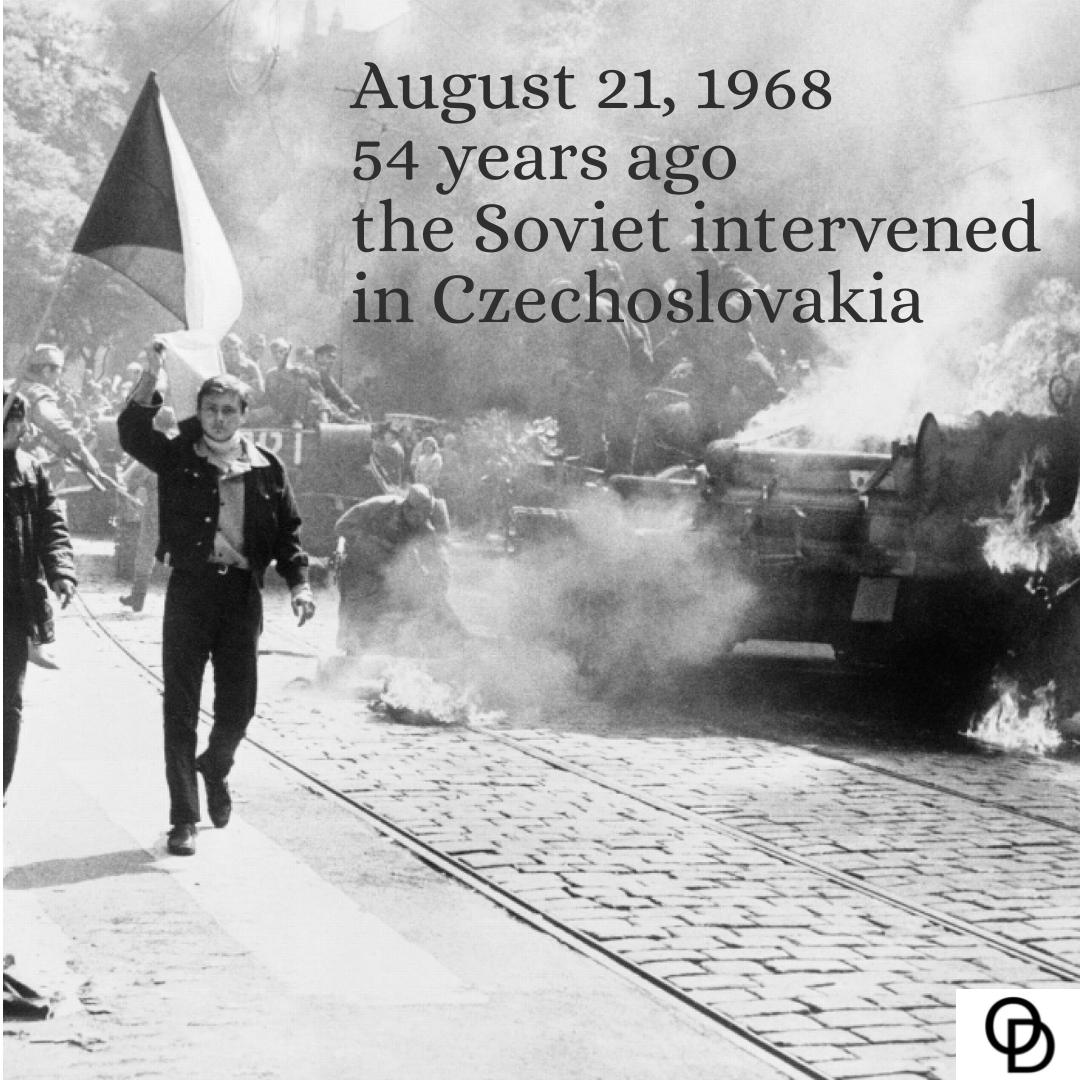

Forty-seven years ago, Soviet troops and their Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia to bring an end to that country’s brief period of political liberalization, called the Prague Spring. About 500,000 troops were involved in the invasion and occupation, during which 108 Czechoslovaks died and some 500 were wounded. The invasion ended the political and economic reforms led by Alexander Dubcek and reasserted dominant Soviet and Communist authority in Czechoslovakia. It also helped establish the Brezhnev Doctrine, which Moscow said allowed the U.S.S.R. to intervene in any country where a Communist government was under threat.

Before the Second World War, the nation of Czechoslovakia had been a strong democracy in Central Europe, but beginning in the mid 1930s it faced challenges from both the West and the East. The Czech economy had been slowing since the early 1960s, and cracks were emerging in the communist consensus as workers struggled against new challenges. The government responded with reforms designed to improve the economy.

The Warsaw Pact invasion of August 20–21 caught Czechoslovakia and much of the Western world by surprise. In anticipation of the invasion, the Soviet Union had moved troops from the Soviet Union, along with limited numbers of troops from Hungary, Poland, East Germany and Bulgaria into place by announcing Warsaw Pact military exercises. When these forces did invade, they swiftly took control of Prague, other major cities, and communication and transportation links. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia was significant in the sense that it delayed the splintering of Eastern European Communism and was concluded without provoking any direct intervention from the West.

There were also long-term consequences. After the invasion, the Soviet leadership justified the use of force in Prague under what would become known as the Brezhnev Doctrine, which stated that Moscow had the right to intervene in any country where a communist government had been threatened.