The most recent assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was published last month, was the most dire ever, issuing a “last warning” and asking decision-makers to take action right away before it’s too late.

How can we reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly enough to prevent a dangerous climate breakdown? is the big question right now.

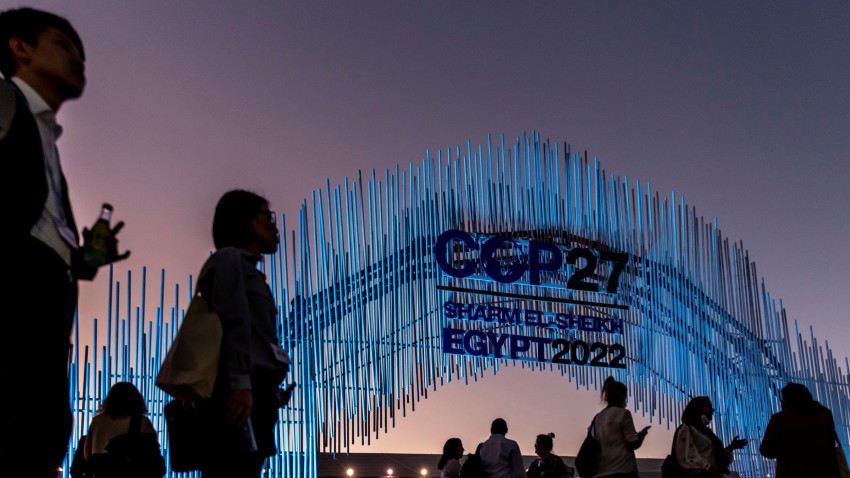

Understandably, worried people and the global world are looking to the upcoming United Nations climate change conference, or COP, which is scheduled to take place in December, for solutions. Yet, the outlook isn’t favourable.

The COP event, now in its 28th year, has established itself as a significant event on the yearly calendar of the global world.

This should, at least in part, give comfort when a climate and ecological emergency is at its worst. The COPs still play a significant role in combating the climate catastrophe, after all.

These not only bring together all the parties involved in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and controlling global warming, or heating as it is more properly referred to.

But they also serve as the sole occasions that will ensure the climate catastrophe is at the top of the global news agenda.

They are no longer functional, which is the issue.

The convention was never signed by the United States, which at the time had the greatest levels of greenhouse gas emissions, while Canada withdrew in 2011 in order to fully utilise its vast supplies of tar sand oil.

In the first commitment period of the protocol, which ran from 2008 to 2012, only 36 countries completely engaged, reducing their emissions by an average of 24 percent below 1990 levels as opposed to the intended 4 percent.

However, emissions elsewhere increased so quickly that by 2010, worldwide emissions had increased by over a third compared to 1990 levels.

The agreement was extended for an additional eight years until 2020 at COP18, held in Doha, Qatar, in 2012, to provide countries time to catch up.

But, despite the COPs’ abject failure to engage and confront the fossil fuel industry, the opposite has unquestionably not been the case. Oil, coal and gas industry representatives have long been eager to slink into climate conferences where they can lobby delegates and officials to advance their cause and obscure the issues as well as seek for new business. The COPs are now severely, if not permanently, discredited as a result.

However, there isn’t enough time to disassemble the entire COP structure and start over. It must be changed instead. One need not be an expert on how best to conduct negotiations to see that doing so under intense time pressure, at the centre of a media scrum.

Even though it might be challenging to implement a ban on fossil fuel industry officials attending future annual COPs.

Every effort should be taken to severely curtail their influence given how disruptive, unpleasant, and even harmful their presence is to the process.

The world is on the verge of a climate catastrophe almost 30 years after the UNFCCC was ratified. Time is nearly up, and we don’t have the luxury of delaying for another three decades.

The COPs must alter immediately if we want to leave our children and their families a world worth living in.